Bringing AI to life

By Catherine Jewell, Communications Division, WIPO

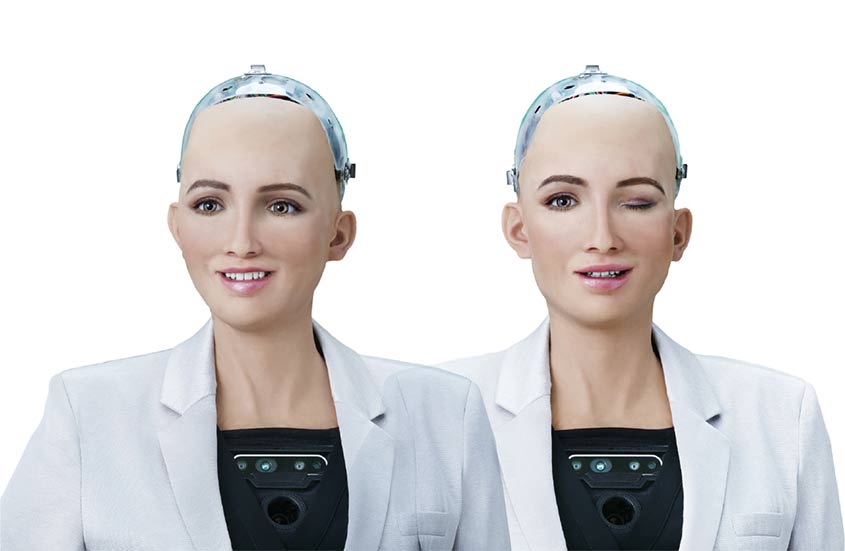

Sophia the Robot, the humanoid robot from Hanson Robotics, has become a global cultural icon. Her maker, David Hanson, CEO and Founder of Hanson Robotics, shares his vision of a future built around superintelligence.

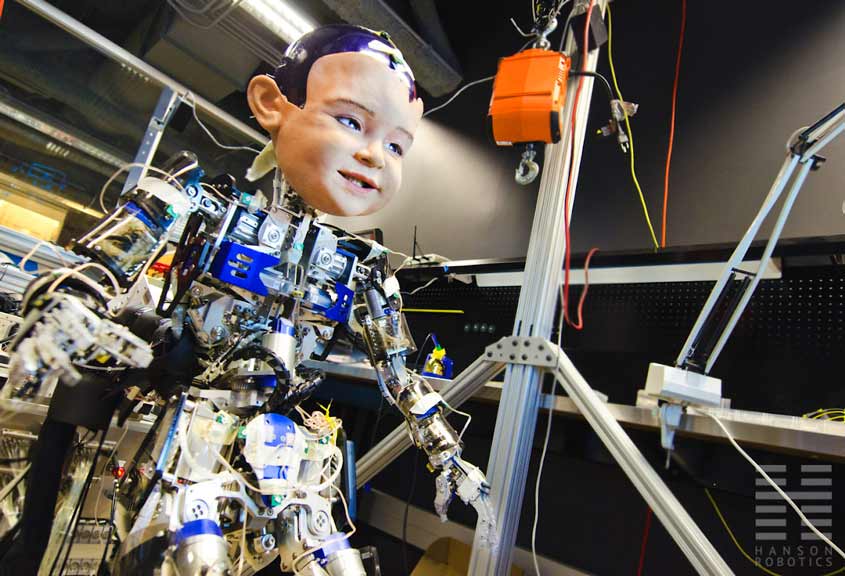

character robot. Sophia leads the company’s mission to make an impact

on humanity through the development of intelligent and empathetic

robots, notes her maker, David Hanson (above right) (photo: Courtesy

of Hanson Robotics).

How did you get into robotics?

I have always been drawn to ask “what if?” and to think about all the ideas that spin out from that. All science starts as philosophy and all technology starts as a dream plus reason. Invention and innovation are about making the unknown known. Ultimately, the development of artificial intelligence (AI) isn’t just powered by technology, but by dreams and discovery.

My path has led me to many interesting disciplines across the arts, sciences, and technology. The interplay of these interests prompted me to start creating humanoid robots as a new artistic medium. I find this very interesting.

I studied a bit of computer science while programming robots, built my first humanoid robot in the early 1990s, and then completed an undergraduate degree in film/animation/video focused on AI-based narrative. I worked as a professional sculptor for a while and then moved into robotics development at Disney Imagineering. After that, I joined a mixed-disciplinary PhD program, which further fueled my interest in robotics.

Can you tell us about Sophia?

Sophia is our most advanced character robot. She has become quite a cultural icon with a global following. She leads our greater mission to make an impact on humanity through the development of intelligent, empathetic robots. We use her in a variety of R&D and service robotics activities, as well as in support of our community outreach and artistic efforts at Hanson Robotics.

Sophia incorporates our most advanced AI software. It allows her to serve as a bold R&D platform and provides her with rudimentary understanding when she holds natural conversations, sees and responds to facial expressions, and adapts to and learns from those interactions. Also, it provides tools for developing her with the character and interactions for specific applications. Creating Sophia’s face, one of the human body’s most complex organs, was a very big challenge, both in terms of hardware engineering and design. Once we master the code to create a full spectrum of nuanced facial expressions, we have a very powerful means of communicating. Most human messaging is visual, unconscious, and informal. Our aim is to unlock and formalize that nonverbal language using AI, and thereby empower machines with better understanding of human emotions. Sophia is a huge step forward in realizing the dream of creating friendly machines that care for humans.

It took around eight years to develop Sophia’s skin and the software and mechanics for her to make realistic facial expressions. Her face now simulates all the major facial muscles.

While Sophia can make eye contact, making her intelligently responsive and interactive to create an empathetic connection with humans is a complex, ongoing challenge.

Sophia now has great hands and arms, which we built, with some narrow categories of high-performance manual dexterity. She can deal a hand of baccarat in 18 seconds and with over 99 percent accuracy! We’re also training her to hold a pen and draw. And with her new legs, built by our friends at Rainbow Robotics, she can walk for up to two hours on a smooth, flat surface.

At present, Sophia is being used for cognitive research and other types of therapy with astonishing results.

What is your vision of the future?

I want to collaborate with others to develop a roadmap for AI that enables us to bring out the best in human civilization and solve the world’s greatest challenges. We need to think big. The idea is to maximize the potential of AI by creating machines with greater than human-level intelligence, creativity, wisdom, and compassion, to achieve a state of superintelligence.

David Hanson on Hanson Robotics

Tell us about your company

We’re based in Hong Kong (SAR) and employ around 50 people, mainly technologists and scientists, with some designers and artists. Four years ago, when investors started taking robotics and AI markets seriously, things began taking off for us. We now have a complete infrastructure for doing R&D and exploring different verticals in service robotics. Our business model focuses on renting, leasing, and maintenance of our robots.

In addition to Sophia and her siblings, we produce a low-cost consumer robot that can walk, make facial expressions, and gesture with its hands. It will come with a camera and compatibility with Raspberry Pi and other programming tools, including Python, so kids can have fun programming and interacting with it. With consumer robots, we can reach more people faster. We’ve also been developing a service robot, which is in testing as a training resource in business and medical fields (e.g. Mabel at the US Center for Disease Control). There’s also quite a buzz around robotic service agents in the banking world and other verticals.

At Hanson Robotics, we’re creating expressive, life-like robots with a view to building trusted and engaging human-robot relationships. We’re exploring what the future might be like with superintelligence. We do this by integrating robotics, AI, the arts, cognitive science, as well as product design and deployment. But ultimately, we need to develop a super internet of AI to optimize the potential of all sentient beings, including humans – and even new kinds of sentient beings – and we think this will form the backbone of the 21st century economy.

What exactly do you mean by superintelligence?

Broadly, superintelligence means greater than human capacities to create, solve problems, and understand the world. We’re talking about super-genius machines that will enable us to solve some of the world’s toughest challenges: poverty; how to get energy without fossil fuels; or how to invent a better education system that doesn’t just train children to memorize facts, but teaches creativity to actualize their potential. With superintelligence, we may solve these problems in ways humans alone cannot.

Hanson Robotics, is a low-cost, playful robot that is designed to inspire

imagination and share Einstein’s sense of humor and vast knowledge

with a new generation (Photo: Courtesy of Hanson Robotics).

Historically, machines have augmented human intelligence. Books, for example, augment our memory, and the printing press spread the memories widely. Now, computing and AI allow us to explore data to identify patterns that can enable us to produce better outcomes. AI unlocks hidden patterns and finds potential. We already use these technologies to produce better crop yields and more accurate medical diagnoses. Imagine what could be achieved with sentient machines. We could look into the mysteries of human intelligence and identify ways to augment it.

Can you tell us more about your proposed internet of AI?

By redesigning the computing infrastructure to create a networked system of superintelligence comprising a web of AIs, we could really boost our understanding of the intricacies of life on the planet. We could apply that understanding to build a world that encourages us to be our best. This is the idea behind SingularityNet – which I co-founded with Hanson Robotics’ chief scientist Dr. Ben Goertzel, and blockchain expert Simone Giacomelli – as an internet of AI for good.

Such a system would be the ultimate mechanism for generating and harnessing the value of intellectual property (IP). It would allow us to track the contributions people (and machines) make – whether data, inventions, or ideas – and ensure they’re rewarded appropriately as an incentive to create more and yield further benefits.

My ideal for superintelligence is to create an AI system that constantly seeks higher standards of universal benefit and makes that quest desirable for all people. To bring people on board, we need to gamify the pursuit of global well-being.

There is so much knowledge that lies fallow in our world and there are win-win transactions waiting to be found. If we have an AI that gets ever smarter and that can work with us, it can help us unlock that value.

Why is it important for robots to be human-like?

Humans are the best example of general intelligence in the known universe. Studying them enables us to develop potentially better models and theories of general intelligence. We have always used technology to better understand ourselves and our place in the universe. Building humanoid robots creates a tool for science and is an interesting artistic exercise.

When we create superintelligent machines we need a positive relationship with them based on mutual respect and trust. A human-like interface makes it easier to create an empathetic connection with humans for enhanced human-robot communication. Ultimately, human-like robots will speak to humans on human terms. The more you train robots in this way, the smarter they will become about the human experience.

Making fully embodied robots that simulate the whole human organism will allow superintelligent machines to learn and evolve like people, much like babies do. It will also allow us to tackle the miracle of emergence. Emergence is wired into math and physics, the base code of the universe. The mechanisms of life and emergence are not yet fully explored and understood, but we have enough understanding of the complexity of emergence in the physics of life, that already we can create kinds of simple artificial life in our computer simulations. Basically, when the conditions of a system are just right, new patterns emerge, as discussed in Stephen Wolfram’s New Kind of Science and Christopher Langton’s Edge of Chaos theory. To achieve machine creativity and true deep intelligence, we probably need to create such conditions. There is already evidence that spontaneous emergence happens in organisms, and appears key to humanlike creativity. We see this in the human nervous system and some deep learning networks. There may be other unknown mysteries of emergence that we can identify using AI and ongoing science that may accelerate the realization of superintelligent machines.

How can you ensure values are instilled in machines?

We have to work to design our machines with values and teach them our best. We may expect that not all species of superintelligence will bring out the best in humanity or serve the survival of life on the planet. So we have to wire the system to represent values around the best long-term survival potential of humans and the biome, and the search for maximum creativity, joy, and human actualization. We need to develop AI that activates a dopamine-reward cycle in people to encourage them to want to achieve truth, survival, creativity, and the greater good. We need machines that work with us to grow wiser too; machines that reveal our actual impact on the environment and humanity, enhance and maximize human wisdom, and help us cross-check and confirm truth, higher values, and assumptions. This will increase the odds that both humanity and AI align with universal values of truth, life, liberty, reduced suffering, and enhancement of creativity.

If we’re smart and dedicated to that principle, we can achieve win-win transactions that make the planet a better and safer place. To do this better requires maximizing intelligence, with a deep commitment to persistently explore possible outcomes in pursuit of maximum benefit. I believe we can best achieve this by working in symbiosis with superintelligent machines. If we don’t achieve these goals and imbue AI with such values, then AI may become dangerous.

What are your views on embedded biases in algorithms?

In computing, we have a maxim: garbage in; garbage out. Computers will learn what you feed them. Any prejudices in algorithms will be learned and amplified. So we have to be careful about the data we feed AI.

There are some exciting developments in the use of AI in automation science that may offer effective ways to reveal these biases. If AI is to be maximally beneficial, then we have to solve this problem.

What’s your approach to intellectual property?

Our policy is 70 percent open and 30 percent proprietary. We release a lot of code as open source. Many people are using it and that’s great! Our quest is to use AI for the greatest good, and ironically our power to influence this kind of open future would be diminished if we were to be completely open source at this point. That’s why we keep some intellectual property for ourselves. But right now, we have the advantage of a fresh, innovative perspective, and are also protected by the combination of artistry and technology we use. I don’t expect that competitive position will last forever and am proud of our achievements so far, but to remain competitive we will have to keep innovating.

What are your next steps?

We’re concentrating on scaling our operations. With our current leasing arrangements, we should be able to do that fairly quickly. Consumer robots and the software and content aftermarket for them present sizeable commercial market opportunities, so we’re looking to secure a foothold there too. We may also consider going public to raise the capital needed to realize the full opportunity of using characters as an interface for AI in robotics services. There’s a huge opportunity here to create an intuitive connection between robots and people.

Today, there are many examples of using AI for good to address specific, narrow issues. That’s good, but I worry that we may not be addressing the big picture well enough. We already have the tools to address some of the deepest questions of our existence. We need to use them and we need to think big.

The WIPO Magazine is intended to help broaden public understanding of intellectual property and of WIPO’s work, and is not an official document of WIPO. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WIPO concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication is not intended to reflect the views of the Member States or the WIPO Secretariat. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WIPO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.